Description

The seventeen pipes of the shō are made of thin bamboo tubes with equal thickness and different length. Because of the different lengths, each pipe has a different pitch. A metal reed is attached to the wooden pipe on the bottom of each bamboo pipe. When this reed vibrates, the air between the reed and the closed upper end of the bamboo pipe resonates and produces sound. Each pipe has a finger hole that needs to be covered for the pipe to emit sound; therefore pipes with uncovered holes are naturally muted.

Finally, the seventeen pipes are set in a circular wind chamber in which air is blown through the mouthpiece, as shown in Fig. 1 and 2.

Shō – front

Shō – front

Shō – back

Shō – back

Figure 1

ISHIKAWA Ko

ISHIKAWA Ko

ISHIKAWA Ko

ISHIKAWA Ko

Shō - Embouchure

Figure 2

The shō cannot produce sound when the reed is moist, so performers must occasionally dry the area where the reeds are attached. To that effect, performers often have on their side an electrical heater as shown in Figure 3.

Electrical heater used to keep the reeds dry

Electrical heater used to keep the reeds dry

Figure 3

Breathing

The shō player producing sound by breathing through the instrument while inhaling and exhaling.

Tuning and transposition

The shō sounds one octave higher than written, and it is tuned to an A-430Hz.

Range and fingerings

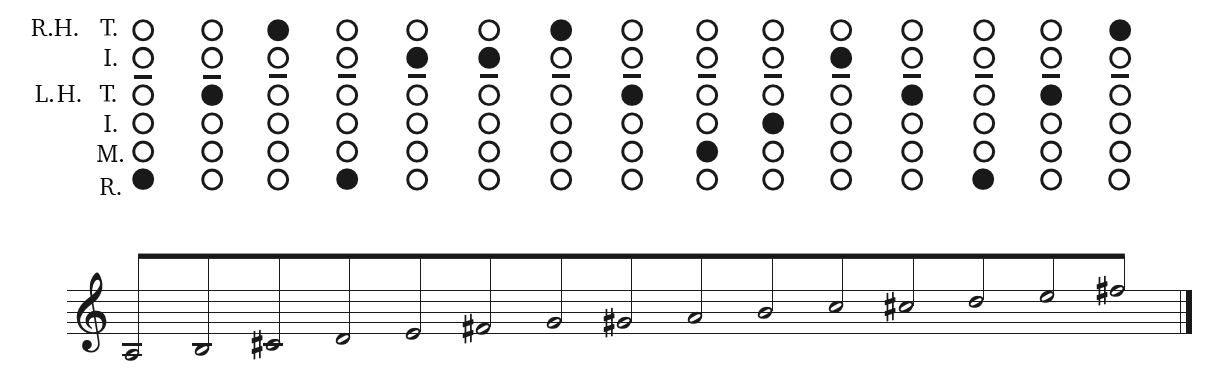

Of the seventeen bamboo pipes, only fifteen produce sound. Figure 4 shows the 15 pitches available on the shō, and their corresponding fingerings. Only the right hand's thumb and index, and the left hand's thumb, index, middle, and ring fingers are involved in the fingerings.

The 15 pitches playable on the shō and their corresponding fingerings

The 15 pitches playable on the shō and their corresponding fingerings

Figure 4

There is a basic fingering rule for the shō stating that fingers assigned to more than one pitch can only play one of them at a time. For example, the A4 and D5 (written A3 and D4) cannot be played simultaneously because they are both fingered with the left hand (L.H.) ring finger. The exception to this rule concerns the index of the right hand (R.H.), which is able to cover the E5 and F#5 (written E4 and F#4) simultaneously.

|

|

|

|

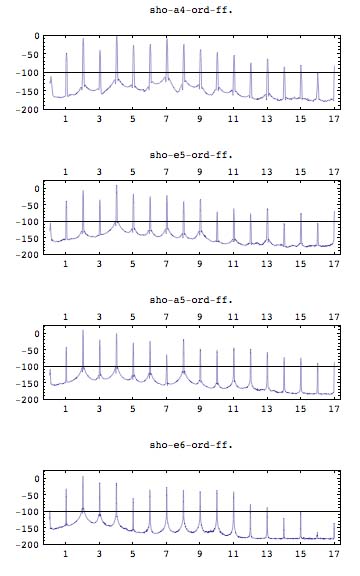

| Four spectra of the sound of the shō | |

Figure 5

Figure 5 introduces the spectra of four sounds from the shō (A4, E5, A6, and E6 : written A3, E4, A4, and E5), which essentially cover its entire range. This helps to illustrate two particularities about the shō’s sound. First, the shō’s spectral envelope barely changes over its entire range, suggesting that its sound is homogeneous throughout its range. This is rather unusual since the sound of a woodwind instrument is commonly darker in its lower register and brighter in its highest register. Yet, a comparative listening of the shō’s lowest note (A4, written A3) with its penultimate note (E6 written E5), confirms the overall uniformity of the shō’s sound.

Figure 5 also reveals that throughout its range the main energy remains essentially on the 2nd and 4th partials of the sound, accounting for the bright and pure quality of its isolated tones.

Traditional performance practices

Articulation: Traditionally, tonguing is not used with Japanese wind instruments. Instead, phrases are shaped by control of the airflow.

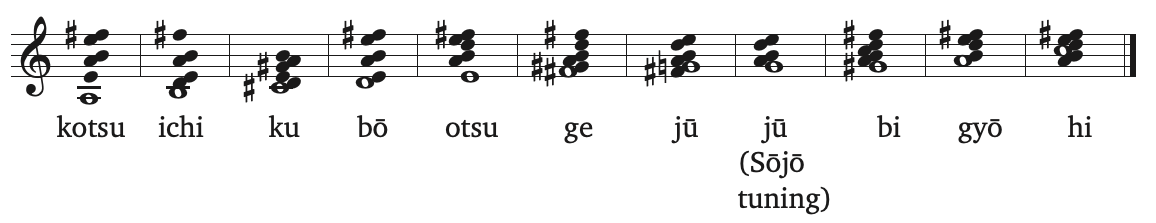

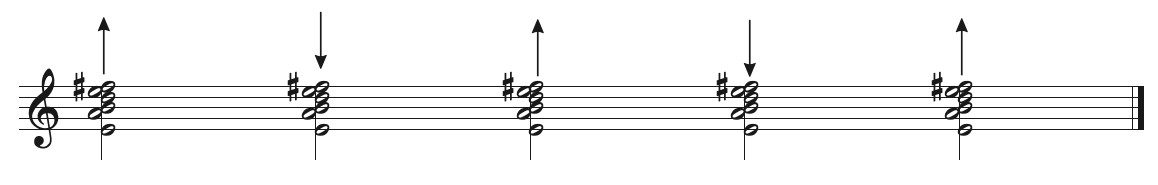

The range of the shō is limited, and the volume of each individual pipe is rather weak. This explains how the function of the shō in the gagaku orchestra is to play chords called aitake. These chords of up to six pitches can be extremely expressive. Figure 6 shows and identifies the eleven chords used in the repertoire. For all of them, except for jū and hi, the lowest note is considered the chord’s fundamental tone and it is shown as a whole note.

11 aitake chords used in tōgaku

11 aitake chords used in tōgaku

Figure 6

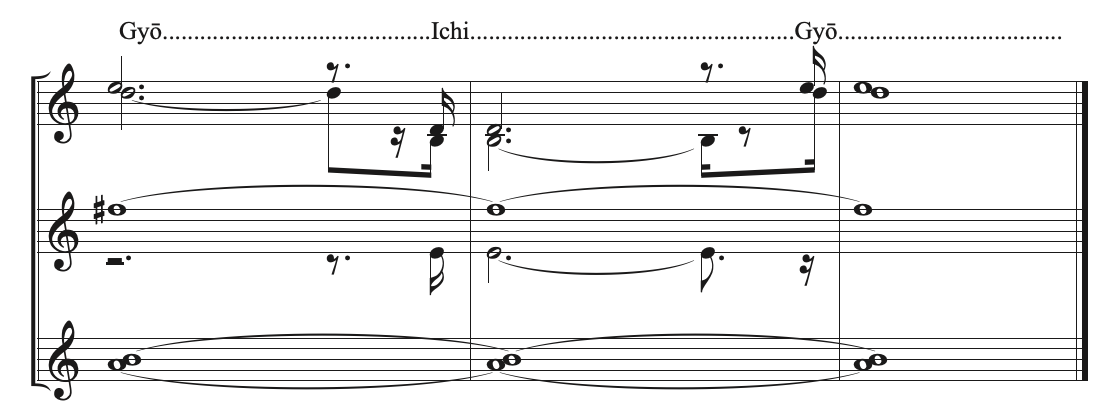

The motion from one aitake to the next is accomplished by a subtle and gradual shift in fingering positions, called te-utsuri. It is sufficient to write the aitakes as chords, and the experienced shō player will know how to perform a melodic and rhythmic transformation from one chord to the other. Although these shifts are melodically and rhythmically set, they are extremely expressive. The following example present a te-utsuri chord transition from gyō to ichi back to gyō.

Rhythmic approximation of the te-utsuri chord change from gyō to ichi back to gyō.

Rhythmic approximation of the te-utsuri chord change from gyō to ichi back to gyō.

Example 1

Example 2 shows the basic melody of Etenraku's section B and C, and its rhythmic accompaniment. Its purpose is to show in context how the shō uses various aitake to color the melodic tones. The phrase structure is of four measures of four beats, and each section is composed of two phrases.The piece is in Hyō-jō mode (E Dorian) and the basic melody is centered on the pitches: E, B, and A, three of the four fundamental pitches of the Japanese modal system.

Example 2 also shows approximations of the shō's motions from one aitake to another. To clarify, the lowest pitch of the shō's aitake is considered its melodic tone. Hence, Example 2 confirms that the shō's harmonic changes are rhythmically in phase with the melodic tones. This being said, the third beat of measure 14 shows that this is not always the case. Here the basic melodic tone, 'A', is harmonized with the aitake based on 'B' (ichi) instead of the one based on 'A' (kotsu). In this context the aitake based on 'B' (ichi) behaves as a passing chord between the aitake ku (C#) and kotsu (A), in using this chord, the shō delays the arrival point of the aitake kotsu (A) so that it can come into phase with the obachi.

The excerpt is performed by the ensemble Reigakusha.

The basic melody of Etenraku's section B and C and how it is articulated by the shō

The basic melody of Etenraku's section B and C and how it is articulated by the shō

Example 2

New performance practices

- Articulation: Depending on performer abilities, staccato, single- double- and triple-tonguing can be used.

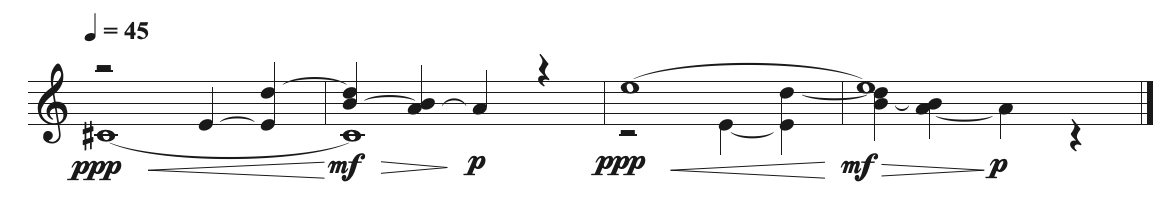

- Drone: While the shō is primarily a harmonic instrument, it can perform melodies and even melodies that transform into a timbre. The use of drone is particularly well suited for this effect. The next example shows a melody accompanied by two different drones from the instrument.

Drone

Drone

Example 3

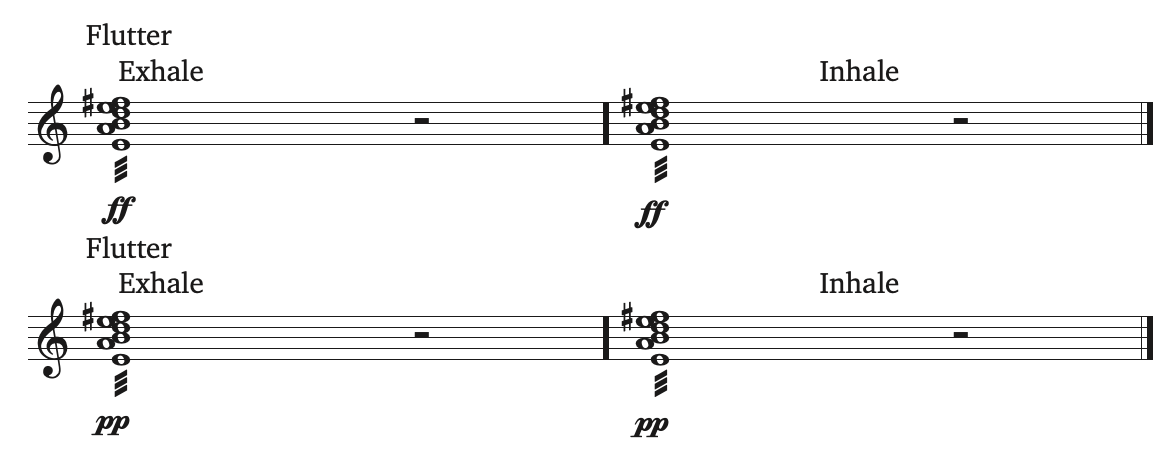

- Flutter tongue: This is a common technique used by a flutist by fluttering his/her tongue to make a characteristic 'Frrrrr' sound. Performing an isolated alveolar trill while playing a pitch produces the effect. This technique is playable throughout the register of the shō. Flutter tongue performed when inhaling has a sound that differs from the sound produced by exhaling, as illustrated in Example 4.

|

|

|

Flutter while exhaling - loud |

Flutter while inhaling - loud |

|

Flutter while exhaling - soft |

Flutter while inhaling - soft |

| Example 4 | |

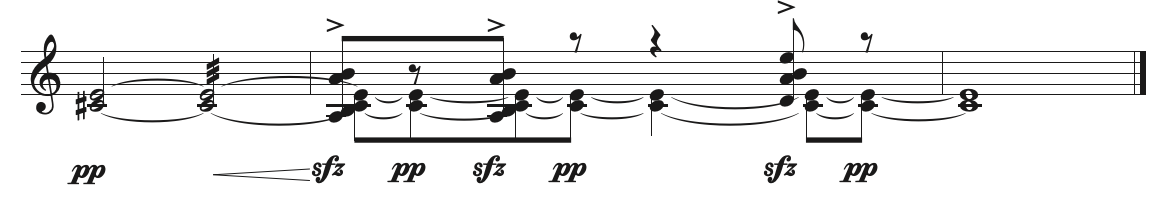

- Attacked chords: The sudden attack of a chord or a rapid change of dynamics over a sustained chord is very effective.

|

|

|

Flutter and attacked chords |

|

| Example 5 | |

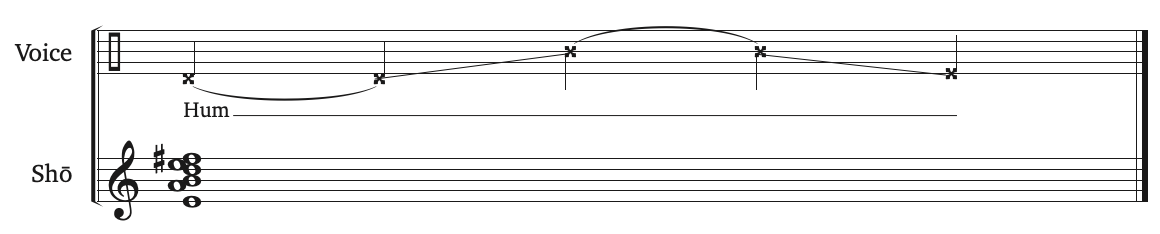

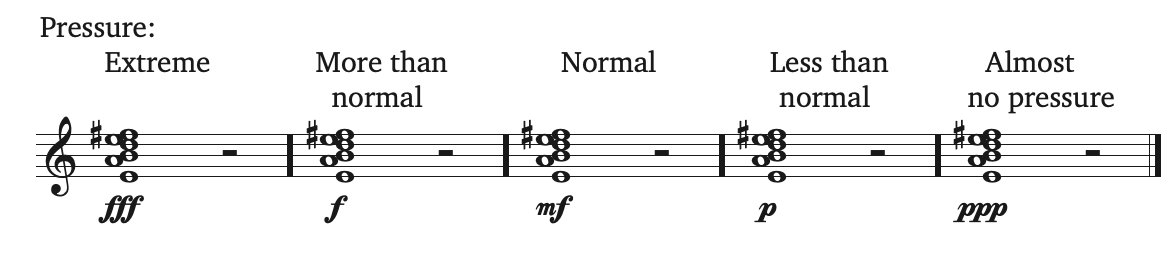

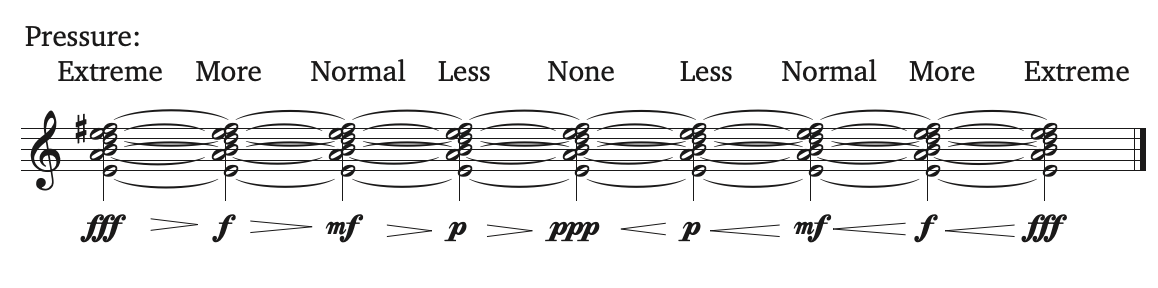

The mexican composer Julio Estrada (b.1943) worked in collaboration with ISHIKAWA Ko to incorporate new techniques for the shō in his opera Pedro Páramo: Doloritas (2006). Some of these techniques involved the use of the voice, blowing with various pressures and vibratos, as well as breathing effects.

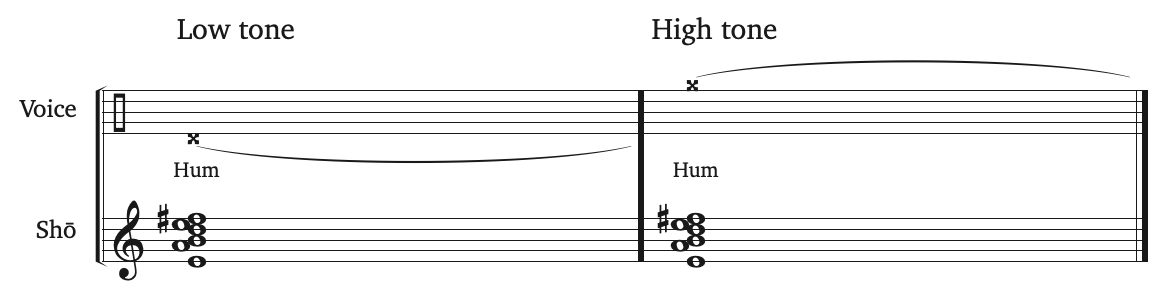

- Use of the voice: It is possible to sing while playing, but control of the pitch is extremely difficult. Results are best when pitches are indicated as low, high, or as gestures rather than precise tones, as shown in Examples 6A and 6B.

|

|

|

Singing a low tone while playing |

Singing a high tone while playing |

| Example 6A | |

|

|

|

Singing vocal gestures while playing |

|

| Example 6B | |

- Use of various pressures: This affects primarily the attack of the sound. As pressure decreases, the synchronicity between the entrance of various tones of the aitake (otsu in our example), breaks apart as heard in Example 7A. The effect is lost when the change of pressure is continuous, as confirmed with Example 7B.

|

|

|

Discrete change of pressure |

|

| Example 7A | |

|

|

|

Continuous change of pressure |

|

| Example 7B | |

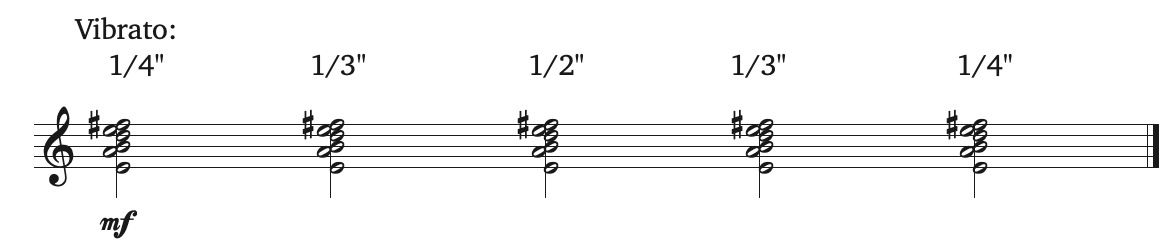

- Various speeds of vibrato: It is possible to indicate a changing speed of the vibrato by either using graphic notation (with changing sinusoidal curves) or by using a ratio that shows that rate of the vibrato. This is demonstrated in Example 8, where 1/2", 1/3", and 1/4" mean respectively, 2, 3, 4 vibrato-beats per second.

|

|

|

Example 8A - Discrete transformation |

|

|

Example 8B - Continuous transformation |

|

| Control off various speeds of vibrato | |

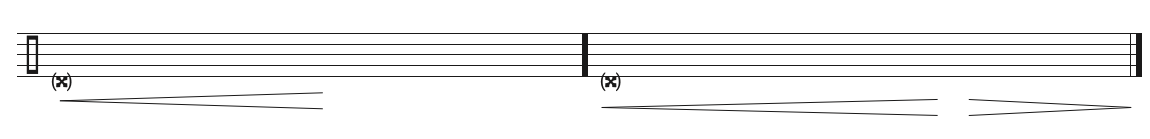

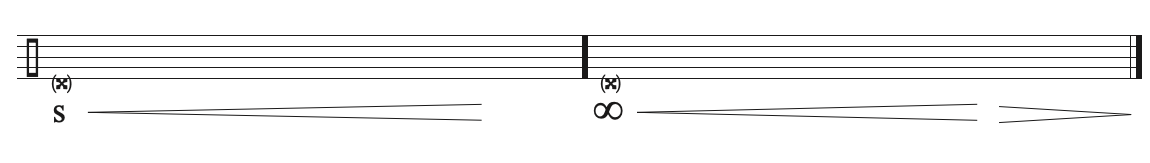

- Breathing: It is possible to create breath noise while playing. The production of 'white-noise' (performed with tight lips) and 'colored-noise' (performed with looser lips but strong breath) is also possible, but not while playing. In all cases, the use of breath is indicated with text in the score, as shown in Examples 9A, 8B, and 8C. The arrows in Example 9A show a breath-in and -out pattern.

|

|

|

Otsu with breathing |

|

| Example 9A | |

|

|

|

White noise |

|

| Example 9B | |

|

|

|

Colored noise |

|

| Example 9C | |