Mixing the three choirs

The seating arrangement for the kangen orchestra is prescribed as shown in Figure 1. Woodwind players sit in the back, with the ryūteki players on the left, hichiriki in the middle, and the shō players on the right. For each instrument, the seating arrangement of the 3 performers forms a triangle, with two players sitting on the back row, and the first chair in front of them. The string players sit in front of the woodwind players, with the two koto players on the left and the two biwa players on the right. In both cases, the first chairs are the ones sitting closer to the middle of the stage. Finally three percussionists occupy the front row with the shōkō on the left, the taiko in the middle, and lastly the kakko on the right. There is no conductor. The 16 musicians synchronize via the melody. The typical training for a musician of kangen music starts by studying one of the three-woodwind instruments for seven to ten years. Then, the musicians add to their training by the study of either a string or a percussion instrument, as well as dance or singing. Therefore, all musicians know the melody and how their part fits in relationship with it.

Reigakusha ensemble

kangen orchestra

Reigakusha ensemble

kangen orchestra

Figure 1

This allows for the musicians to change their roles. For example, during one of our working sessions with the ensemble Reigakusha, as they were switching from kangen to bugaku music, the shō player ISHIKAWA Ko had left his instrument for the taiko, while the hichiriki player NAKAMURA Hitomi had left hers to put on a costume in preparation for a dance she was about to perform. Through a rigourous training, the kangen musicians memorize the melody of the ninety-nine works that have survived the passage of time. Each musician learns their part in relationship with the melody. Thus it is the wind instruments, not the percussion that control the temporal unfolding of a piece, that is why they sit in the back, whereas the percussionists sit in the front.

Form and instrumental textures

The orchestration of the introduction and coda sections of every kangen piece is presecribed, and static for the rest of the work. The first and the last sections act as a gradual fade-in and fade-out, and only the first chairs play in these sections. The instruments enter in the introduction following a preset order: the ryūteki enters first, followed by the percussion instruments, then the shō, which enters simultaneously with the hichiriki, and finally the biwa and the koto. After the equivalent of about a phrase-length of solo playing, each first chair is joined in by its respective peers. Hence, the entrance of the second koto completes the tutti that is invariably maintained until the coda. At that point, the instruments disappear following another preset order. The percussion instruments stop first, followed by the woodwind instruments, and then the biwa and koto.

Register

The traditional separation of the choirs based on their acoustical properties and different functions is emphasized by their separate registers, where the string and woodwind instruments occupy two separate ranges.

The beauty of kangen music

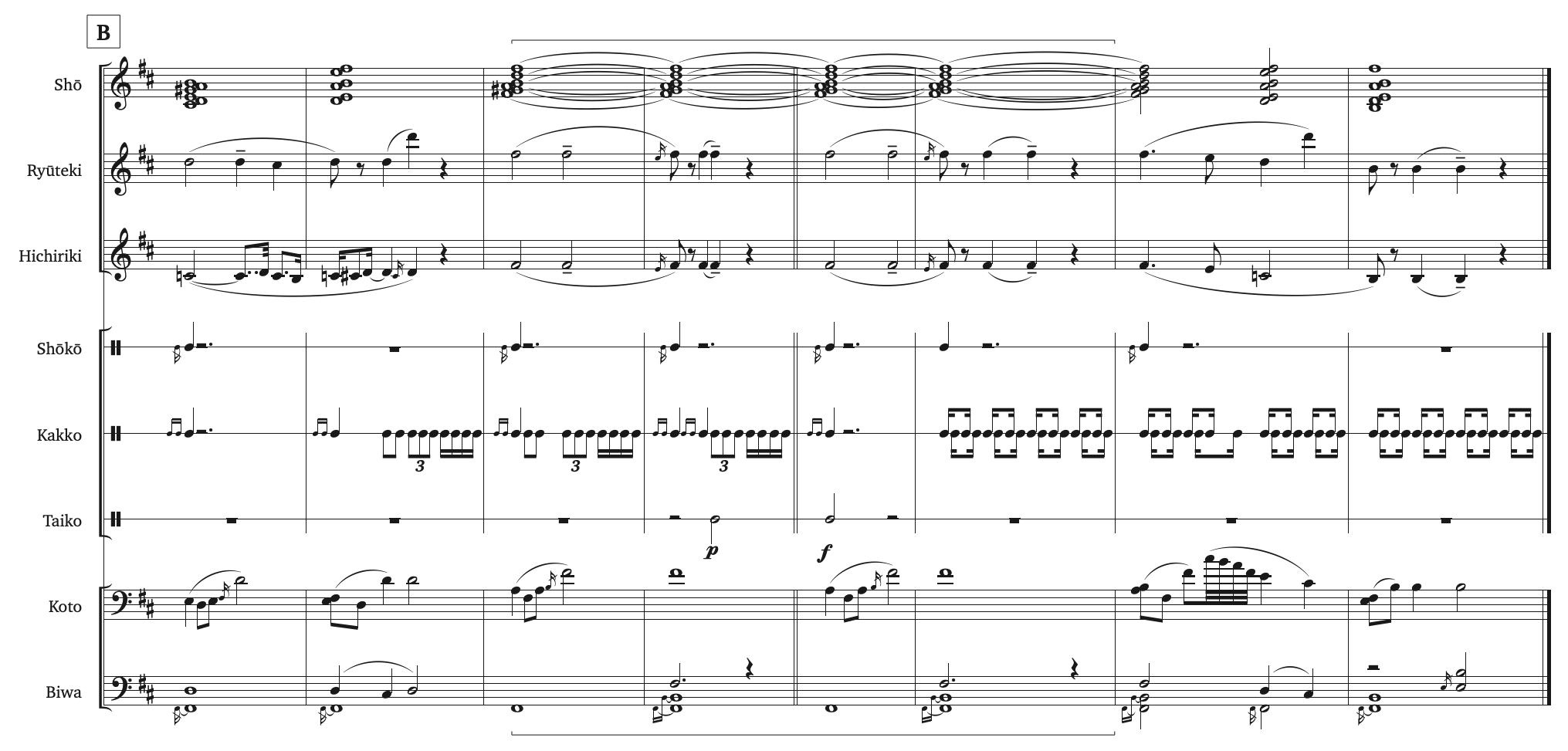

Example 1, an excerpt from Seigaiha, shows phasing interplays between phrase structure and timbral transformation, thus adding one more dimension to the music.

Simplified notation of Seigaiha's first phrase of Section B (measure 17-24)

Simplified notation of Seigaiha's first phrase of Section B (measure 17-24)

Example 1

Seigaiha's phrase structure is eight-measures long, with four beats per measure. That structure is established with Section A’s two phrases, where we find the expected four measures of the melodic motion to have an overall color favoring the woodwind instruments, coming to a sustained-tone at the phrase’s mid-point, in phase with the obachi. After this, the overall color switches to a mixture of shō and string instruments.

The synchronization between the music’s phrase structure and its timbral transformation is broken in the first phrase of Seigaiha’s Section B, as shown in Example 5. The 4+4 measure pattern has switched to a 2+4+2, with the sustained-tone on F# starting two measures before the obachi, setting a feel of ambiguity, which is maintained in the second phrase of Section B, where an eight-measure melodic motion is introduced without a sustained-tone. Finally, the phasing between the two groups is re-established with the first phrase of Section C. (These last two phrases are not shown).

The 2nd phrase (measure 8-16) of Konju-no-Ha provides another example of a method of out-phasing the phrase structure and the sound transformations. The phrase cycle is four-measure long with four beats per measure, as shown in Example 2.

Konju-no-Ha: 2nd phrase (measures 9-16)

Konju-no-Ha: 2nd phrase (measures 9-16)

Example 2

The melodic line of this phrase does not utilize the standard 4 + 4 where each four measures are further divided in 2 + 2. Instead, the lines merge two groups of four measures into 6 + 2, and consequently, there is no change of timbre that corresponds with the first obachi. The sustained-tone of the last two measures is phased-out, starting two beats earlier than the obachi.

Our purpose with these last two examples is to point out a particularly lively aspect of kangen music. We hope that it will help the listeners go beyond the first impression of overall static sonority and notice the unique beauty of its timbral and strucutral transformations.

Timbre and time

Like its Western Classical counterpart, kangen orchestral music is composed of superposed layers of sound. While Western orchestra layers usually blend, layers of gagaku orchestral do not. The listener can at all times easily differentiate the sound of instrumental choirs, as well as instrumenta within each choir. The intricate and refined interaction between the eight kangen instruments is clearly perceptible at every moment. This provides a complex and dynamic experience, even through on a larger scale other elements appear slow or static. The richness of kangen music is not based on a high level dramatic development but on the inner life of the present moment.

This research has focused mostly on timbre and on orchestration in kangen music. We would like to refer the reader also to our article written on the correlation between timbre and time in kangen music: Japanese Traditional Orchestral Music: The Correlation between Time and Timbre.