Description

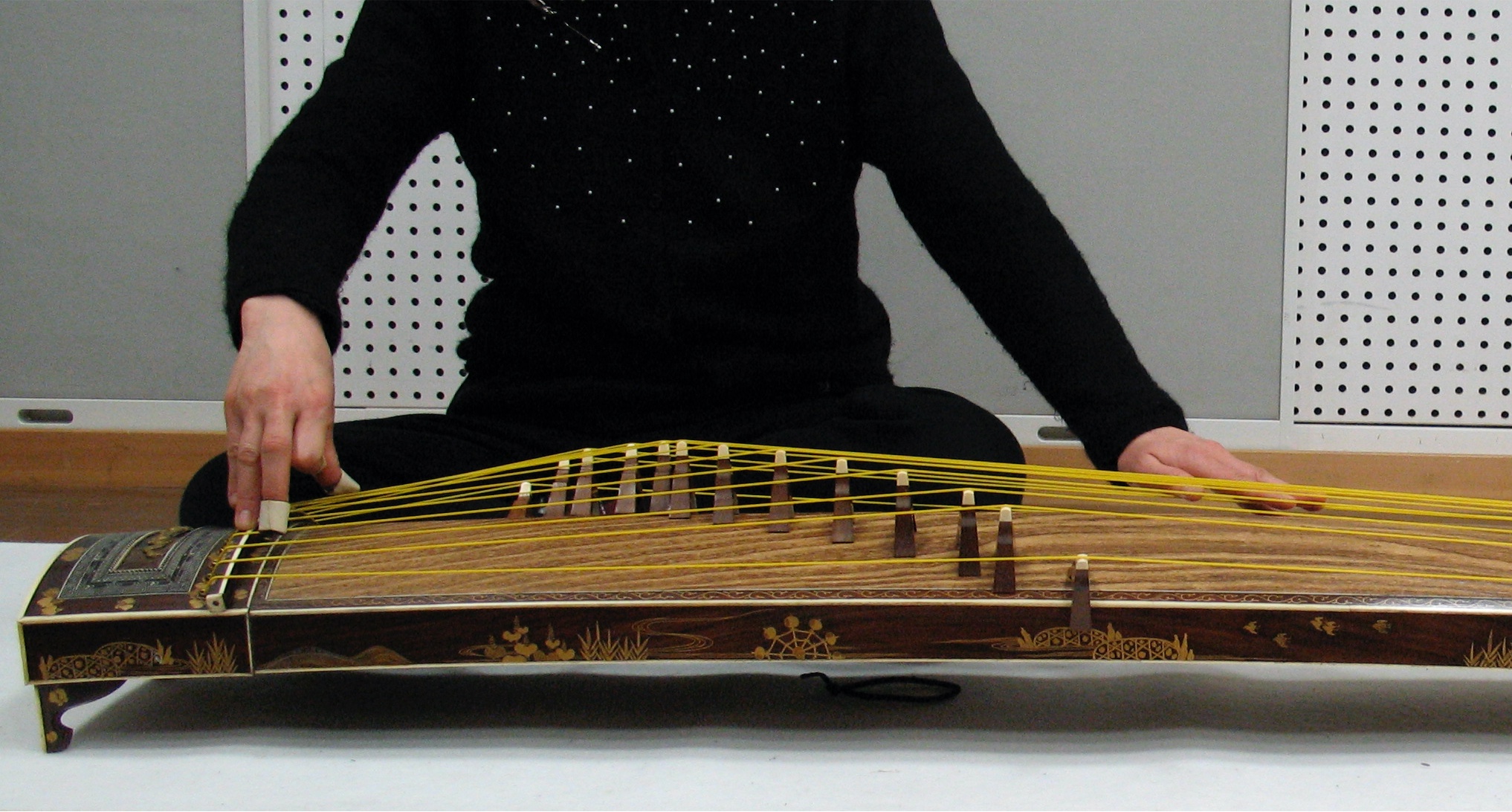

The koto is a thirteen-string zither, approximately 190 cm long and 25 cm wide (75 inches long and 10 inches wide).

Koto

Koto

Figure 1

Tuning

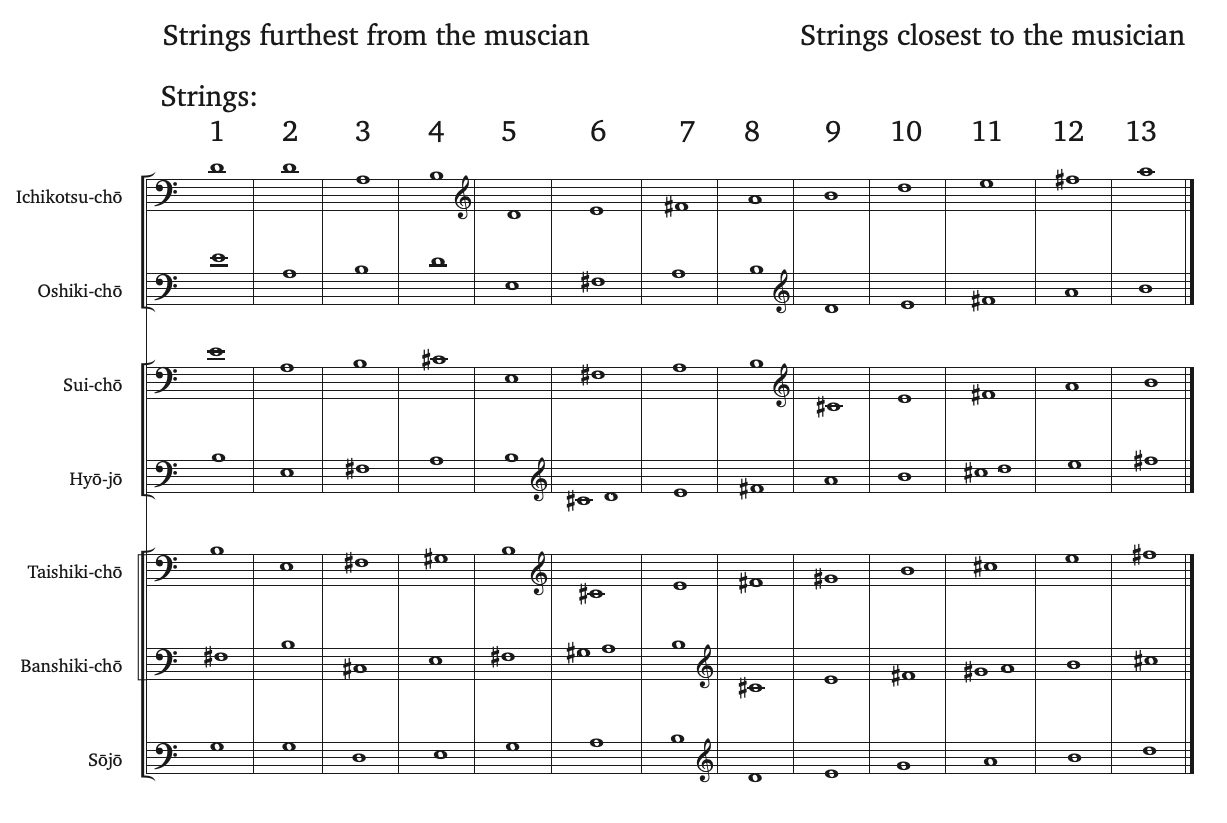

The koto sounds as written, and it is tuned to an A-430Hz. The strings are numbered from the lowest (first string - outer) to the highest (thirteenth string - the inner, closest to the musician).

Tuning is accomplished by changing the position of the movable bridges under the strings, which are plucked with plectra placed on the thumb, index, and middle fingers of the musician's right hand.

The plectra used for the perfromance of gagaku music are quite different from those used in zoku-sō (secular koto music, Yamada-ryū and Ikuta-ryū), which was developed after the 17th century. In gagaku, a plectrum is made of a relatively small bamboo piece, which is fixed onto a round bandmade of animal skin. The popular left hand technique used in zoku-sō music such as pressing or pulling a string to modify its pitch was used in the performance of gagaku music during the Heian period but since then that practice has been lost. Nowadays, the left hand simply rests on the instrument's table.

Hand technique with plectra in the right hand's fingers, and resting left hand

Hand technique with plectra in the right hand's fingers, and resting left hand

Figure 2

HIRAI Yuko

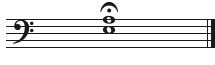

Koto's tuning

HIRAI Yuko

Koto's tuning

Figure 3

Figure 3 introduces the koto's seven traditional tunings. In Banshiki-chō and Hyō-jō, there are two tunings, one for ritsu tuning and the other for the ryo tuning. The former uses respectively A and D for the 6th and 11th strings, while the latter uses G# and C#.

Although the sound of the koto resonates more than the biwa's, three observations can be made about it:

- The plucking position of the right fingers must be as close as possible to the bridge to ensure maximum volume.

- There is a difference in the sound quality between the attack of the thumb and the other two fingers. The thumb attacks the string by upward motion while the two other fingers attack the string by downward motion, and because there is more strength in a downward attack, the two fingers create a stronger sound than the thumb's attack.

Position of the right hand and the downward plucking motion of the index and middle finger.

Position of the right hand and the downward plucking motion of the index and middle finger.

Figure 4

Upward plucking motion of the thumb

Upward plucking motion of the thumb

Figure 5

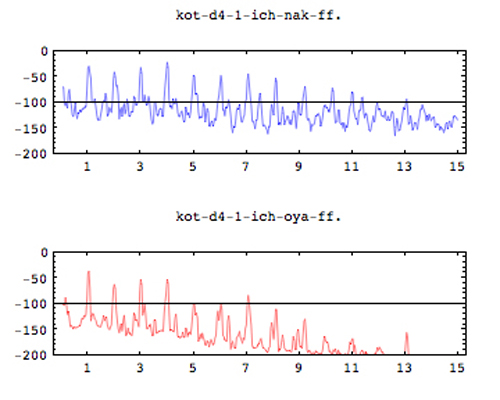

Figure 6 shows the spectra of a D4 played ff plucked with the middle finger (in blue) and the thumb (in red). The sound quality of a pitch attack by the middle finger is richer than when attacked by the thumb.

Comparison of the sound quality of a D4 when attacked with the middle finger (in blue) and the thumb (in red)

Comparison of the sound quality of a D4 when attacked with the middle finger (in blue) and the thumb (in red)

Figure 6

- As seen under 'Traditional performance practices', most of the koto's melodic patterns involve the octave, not only because it falls well under the hand, but also because it provides maximum resonance.

Traditional performance practices

The koto has two types of patterns: metrical and non-metrical patterns.

Metrical patterns

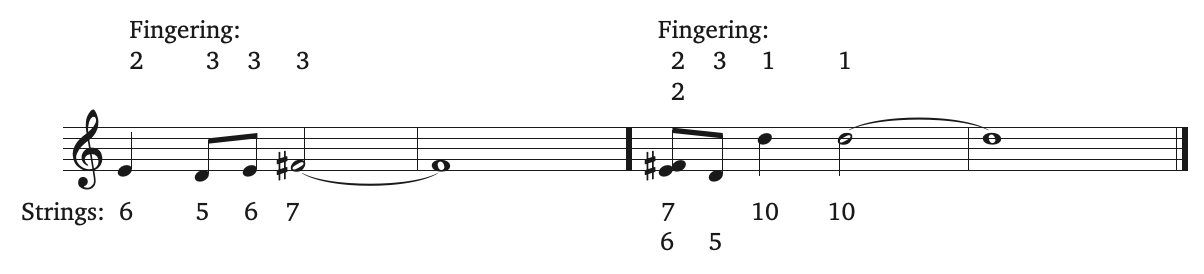

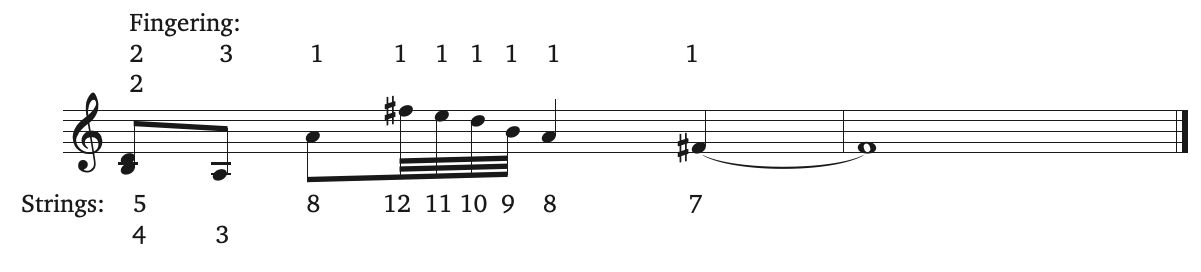

Most metrical patterns are two-measures long. There are two basic patterns that fit this category: shizugaki and hayagaki (The examples are in the Ichikotsu-chō mode (D mixolydian))

a. Shizugaki starts its rhythmic activity on the 2nd beat of the first measure

b. Hayagaki starts its rhythmic activity on the 1st beat of the first measure

| Shizugaki | Hayagaki |

|

|

| 1 = R.H. Thumb, 2 = R.H. Index, 3 = R.H. Middle finger. | |

Example 1

These patterns can be transposed to any of the pitches from the mode, but the fingerings and the string sequences remain the same. Because of the idiosyncratic tunings of this mode, such transpositions do not always generate the same intervallic sequences, as illustrated in Example 2 which demonstrates a transposition of Example 1.

|

|

| Shizugaki transposed | Hayagaki transposed |

Example 2

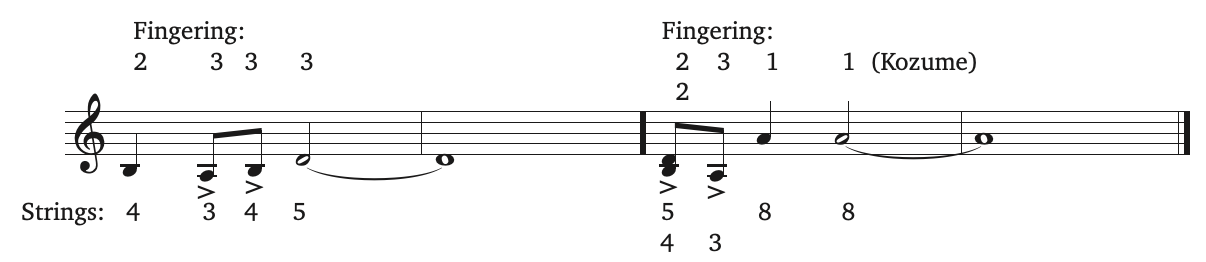

There are various techniques to embellish and vary the basic sounding pattern of the koto, such as, among others: use of grace notes: kozume, sawaru, and ren.

- Grace-note: The pitch of the 2nd beat of the first measure of the shizugaki pattern is emphasized in three ways: First, this pitch is accentuated with a strong attack of the middle finger, and second, it is repeated one octave higher on the third beat. Finally, the last pitch, which is the highest one in the melodic pattern, is preceded by a grace-note that has the effect of accentuating it.

| Grace-note variation of shizugaki |

|

Example 3

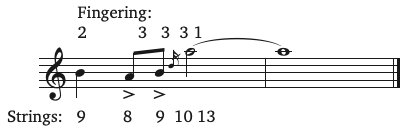

- Kozume: This is a special type of attack from the thumb attacking the string from underneath. The resulting sound is softer than the usual thumb's attack from above. When used with the shizugaki pattern it appears on the 1st beat of the 2nd measure. When used with the hayagaki pattern it can either appear on the 3rd beat of the first measure (like in Example 1) or on the 1st beat of the 2nd measure (Example 4).

| Shizugaki with kozume | Hayagaki with kozume |

|

|

Example 4

- Sawaru: This is a softer attack of the thumb of the 4th beat on the first measure, using the standard upward motion. It is used with both patterns. Here is an example from the work Shukōshi in Sōjō (G mixolydian) mode with the shizugaki pattern.

| Shizugaki pattern with sawaru |

|

| Example from Shukōshi in Sōjō mode |

Example 5

- Ren: This is a glissando performed by the thumb, and it can be used with both patterns. It is most often used as a group of four 32nd notes on the up-beat of the 2nd beat of the 1st measure, leading to the 3rd beat as shown in the example.

| Hayagaki with ren |

|

Example 6

- Musubute: This is a three measure pattern used only in three works: Bairo, Somakusha, and Manzairaku. The first measure of the pattern introduces a special technique of the thumb called kaeshizume.

- Kaeshizume: This is a sequence of attacks from underneath the strings by the thumb. This technique is not exclusive to the musubute pattern, and it can be used with the shizugaki and hayagaki patterns, in which case it appears as two eighth-notes on the 4th beat of the 1st measure.

| Musubute (kaeshizume is used in the first measure of this example) |

|

| Excerpt from Bairo in Hyōjo mode |

Example 7

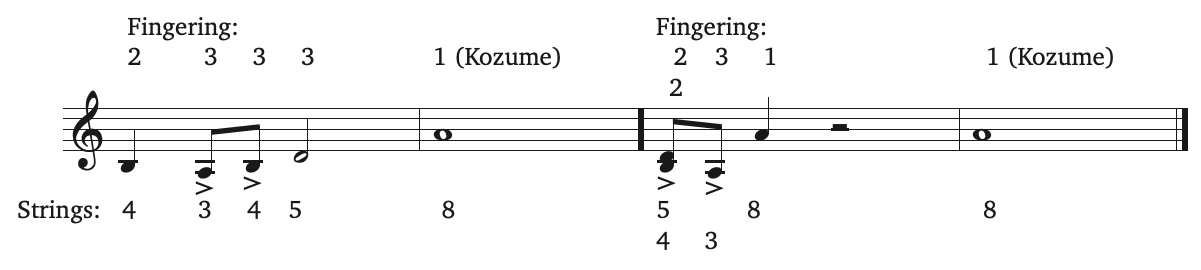

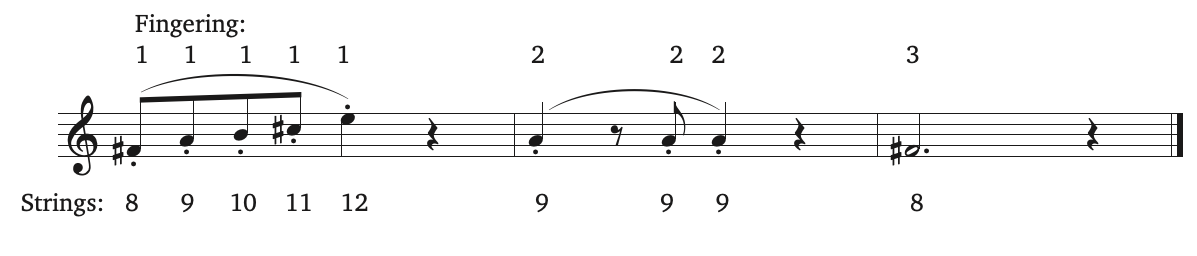

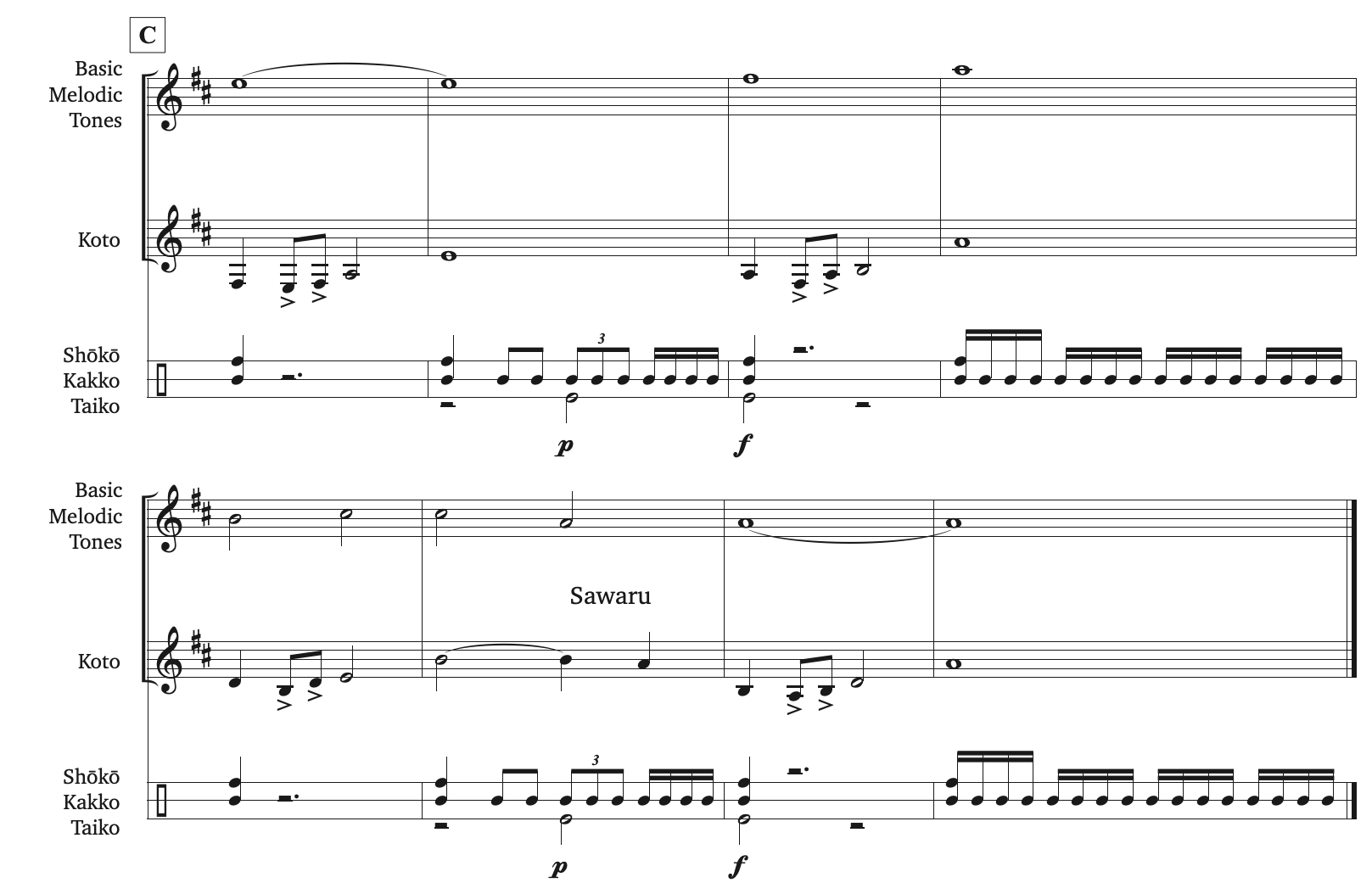

Example 8 shows the koto’s accompaniment to the hichiriki’s part, playing the melody for Etenraku’s sections B and C in concert pitch. The phrase structure consists of four measures of four beats each, with each section composed of two phrases. The piece is in the Hyō-jō mode (E Dorian), and the basic melody centers on the pitches E, B, and A—three of the four fundamental pitches of the Japanese modes.

The koto’s part in Example 8 is articulated with a two-measure pattern: shizugaki + kozume, which colors certain melodic tones. Typically, the two patterns duplicate the melodic tone found on the downbeat of their respective measure. The shizugaki pattern duplicates it on its second beat, while the kozume pattern usually duplicates it on the measure’s downbeat, remaining in rhythmic phase with the melodic tone.

The excerpt is performed by the ensemble Reigakusha.

The basic melody of Etenraku's section B and C and how it is articulated by the koto

The basic melody of Etenraku's section B and C and how it is articulated by the koto

Example 8

Non-metrical patterns

Typical unmeasured sections in kangen music include the netori and the 'coda' (the end of the piece). The netori is a very short piece played in free rhythm taht starts any performances of kangen. It allows the instruments to tune to the shō and adjust to the mode. The koto has two patterns that it uses exclusively in these sections:

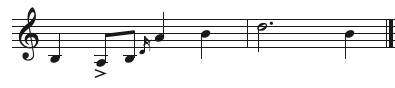

Sugagaki: This pattern can be played in the coda or in the netori of the Taishiki-chō mode. Its melodic shape can be transposed on any pitches of the mode. It has several rhythmic variations including one where the four pitches all have the same duration.

| Sugagaki |

|

Example 9

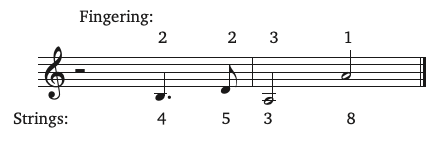

Tsumu: This is a pattern used exclusively in the netori. Beyond that, it is exclusive to the modes that have scale degree 5 and 1 on their 5th and 7th strings, respectively. Consequently it is only used in the netori of the following modes: Hyō-jō, Taishiki-chō, Banshiki-chō, Sui-chō, and Oshiki-chō. The 5th and 7th strings are plucked together by the thumb and middle finger, with the hand positioned slightly away from the bridge, which produces a rather soft sound. The function of tsumu is to help with the tuning process of the netori, since the koto's sound is the most resonating of the two string instruments, and this pattern emphasizes the two most important pitches of a mode: its tonic and dominant.

| Tsumu in Oshiki-chō |

|

Example 10

Tsumu is always part of an unmeasured melodic/harmonic line. Example 10 shows a rhythmic and melodic approximation of a koto part for a netori in Oshiki-chō.

Koto part for a netori in Oshiki-chō.

Koto part for a netori in Oshiki-chō.

Example 11