Mixing the string instruments

The sole function of the string instruments with the shō is to supply harmonic support. The two string instruments work in collaboration to create the pattern that acts as bridge between the woodwind and percussion instruments, coloring key unpitched percussive attacks with pitched motives and harmonies relating to the melody.

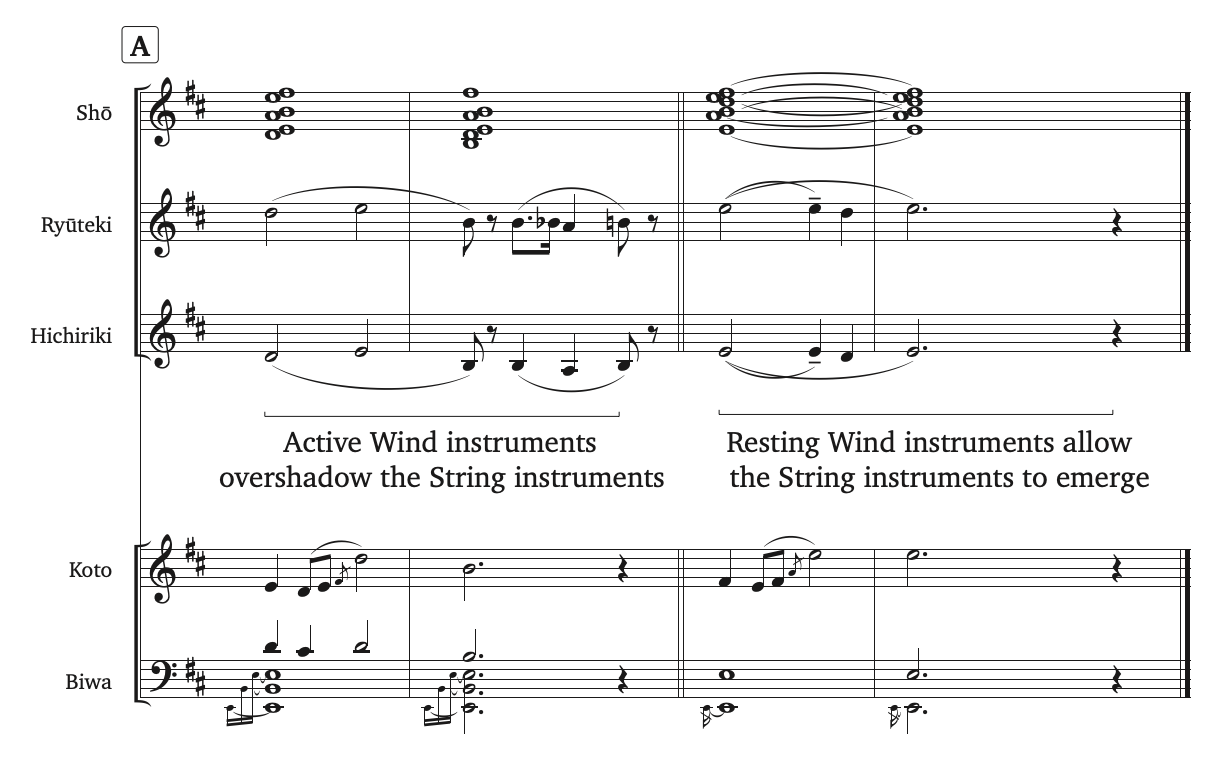

The string section has its own internal hierarchy, where the biwa's main function is to color the downbeat of every measure with an arpeggio. As such, it connects with the shōkō -- the percussion instrument whose function is to articulate the downbeat of every measure. On the other hand, the koto's pattern is usually spread out over two measures, and it slowly spells out the biwa's harmony while reinforcing the main melodic tone. Its rhythmic periodicity therefore puts it in phase with the kakko, the percussion instrument whose accelerando are also spread over two measures. Unlike the biwa whose harmonic support is in phase with the melodic tones of ryūteki and hichiriki, the harmonic support of the koto is out of phase, as shown in Example 1. The hichiriki and the ryūteki introduce ‘D’ as the melodic tone in the first measure, as shown with the arrows. That pitch is reinforced on the same beat by the shō and the biwa. Note that traditionally the lowest pitch of the shō's aitake and the highest pitch on the biwa and koto's patterns are considered to be their principal melodic tones. The biwa's tones ‘E’ and ‘D’ are reiterated in the koto's line with an emphasis being put on the ‘D’, which is the lowest and highest note of the harmony, as shown with the arrows. The recorded example comes from the beginning of the work, and the koto only enters in the 3rd measure. This example is an excerpt from a recording by the ensemble Reigakusha.

|

| Etenraku: Simplified notation of the 1st phrase of Section A (measure 9-12) |

| Example 1 |

Although the biwa and the koto are united in their function, their sounds never fuse. In fact, the sound of the two string instruments usually is a stratified texture where each of the two sounds is clearly distinguishable. There are two factors that work against their fusion: First, a minimum of resonance is required to get some fusion between two sounds, but the sound of the biwa does not resonate much beyond one second; Secondly, our ability to hear separate parts increases when instruments are not synchronized rhythmically, which is the case of these two string instruments. The biwa's activity focuses mainly on the downbeat of every measure, while the koto's main rhythmic activity is focuses on the 2nd and 3rd beats of the first measure when using the shizugaki pattern or on the 1st, 2nd and 3rd beats of the same measure when using the hayagaki pattern.

The beauty of kangen music

he harmonic structures of the string instruments are in melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic relationship with the melody of the two woodwind instruments. Moreover, the string instruments’ pattern adds another level of transformation to the overall timbral structure of the music. Usually, melodies of kangen music divide the phrase in two symmetric parts. The first one featuring some melodic motion followed with a sustained-tone starting at the phrase’s mid-point in phase with the obachi. Thus, the melodic first half of the phrase favors the woodwind instruments, and as the melodic instruments come to a point of rest in the second half of the phrase, emphasis switches to the rhythmically active string instruments. This process creates a cyclical transformation of timbre, as the music moves from melodic motion with the woodwind instruments to harmony provided by the string instruments. This is illustrated in Example 2 with Etenraku’s first phrase of Section A.

Etenraku: Simplified notation of the 1st phrase of Section A (measure 49-52), String and Woodwind instruments only.

Etenraku: Simplified notation of the 1st phrase of Section A (measure 49-52), String and Woodwind instruments only.

Example 2